Introduction

Antibiotics are essential antimicrobial medicines used in aquaculture when a bacterial disease outbreak occurs, supporting stock health and welfare. Crucially, however, the efficacy of antimicrobials is threatened by the emergence, selection and enrichment of antibiotic-resistant microorganisms, which is in turn driven primarily by antimicrobial usage (Allel et al. 2023).

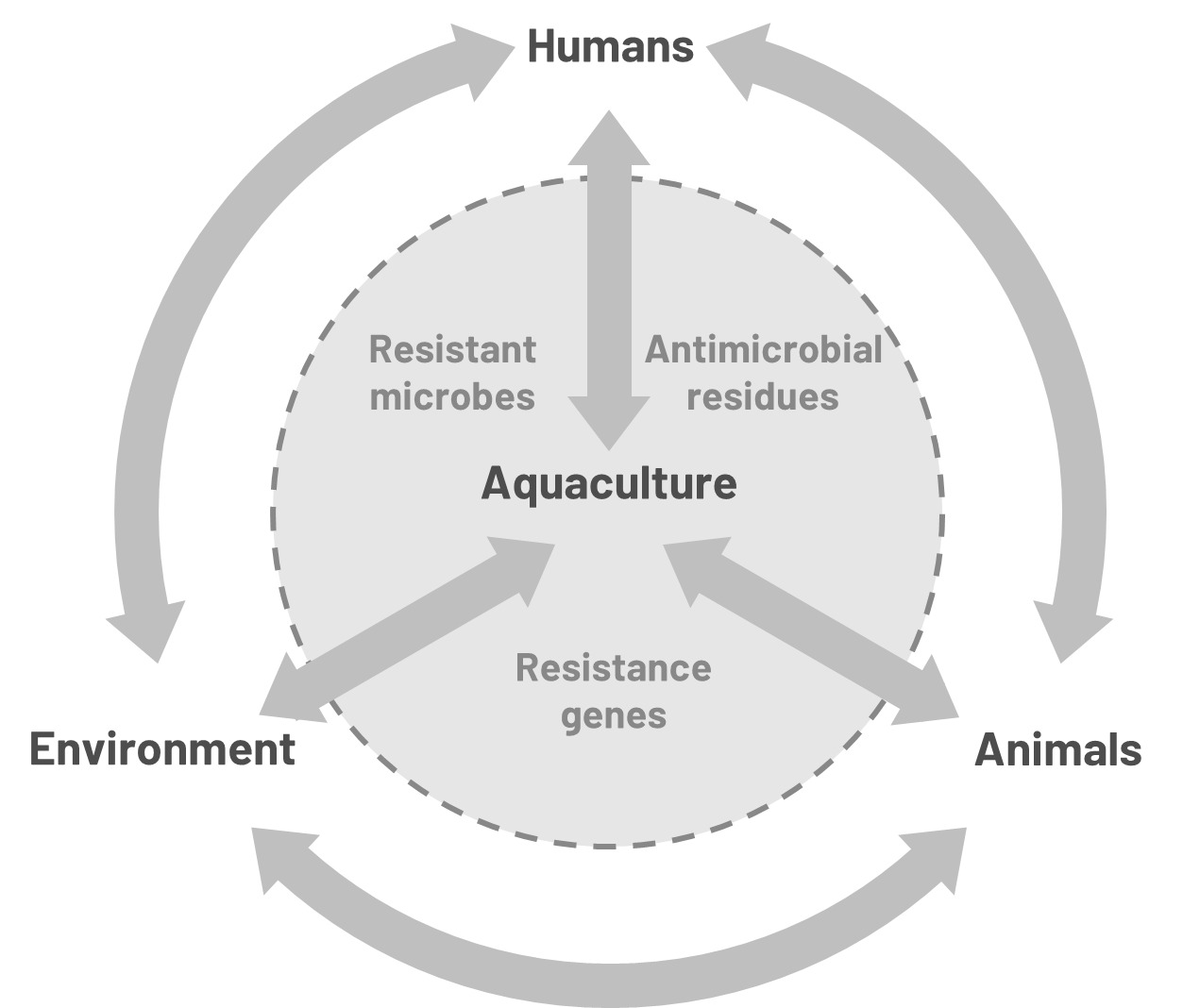

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global One Health challenge with impacts across human, animal and environmental health because resistant microorganisms, and the genes that encode these phenotypes, can emerge in any of these domains but spread to exert detrimental effects in another (Figure 1). Aquaculture plays a role in AMR and potentially sits at the nexus of One Health domains: The commonly open nature of aquaculture systems means they are highly interconnected with the other domains, potentially disseminating antimicrobial residues and resistant microorganisms (Watts et al. 2017; Brunton et al. 2019; Reverter et al. 2020; Limbu et al. 2021; Green and Desbois 2025) (Figure 1). Therefore, it is essential that aquaculture be included in mitigation efforts (Bondad-Reantaso et al. 2020; Desbois et al. 2025).

AMR requires concerted international action across sectors and mitigation efforts are led globally by the Quadripartite comprising the World Health Organization (WHO), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The Global Action Plan on AMR (GAP), developed in 2015 and adopted in 2016, outlines a framework for coordinating actions internationally (WHO 2015). The document provides a platform for each country to produce a National Action Plan on AMR (NAP) to describe what it will do to tackle AMR (WHO 2015). Notably, the GAP is currently undergoing revision, and a new version is expected to be published later in 2025 (Hsu, Legido-Quigley, and Chua 2025).

This short article aims to raise awareness of NAPs, particularly of what they are and what they mean for actors with roles to ensure aquatic animal health and welfare. Heightened awareness for NAPs should allow actors to anticipate and plan more effectively for changes in national policies relating to AMR, while these documents also provide a guide for innovators and the research community to contribute to achieving NAP objectives.

What is a NAP?

A NAP is a high-level strategy document developed by a national government to define how the country will address AMR for the next five years or so. NAPs outline steps to be taken across government to achieve objectives that contribute to this vision, with each NAP developed to account for the country’s unique needs, resources and present situation. To date, more than 140 nations have deposited a NAP in the publicly-accessible Library of AMR National Action Plans (WHO 2025), although many other countries also have published NAPs which are available elsewhere. NAPs evolve and countries refresh their plans approximately every five years; for example, the UK has published several iterations including versions that pre-date the GAP (Department of Health 2000, 2013; UK Government 2019; Department of Health and Social Care 2024).

Typically, a NAP is prepared by a lead government department in consultation with key sectors, mainly users of antimicrobials such as healthcare and food production, because effective action to mitigate AMR necessitates a whole-of-society approach (Hsu, Legido-Quigley, and Chua 2025), and the One Health philosophy requires actions to be taken across human, animal and environmental domains (WHO 2015; FAO et al. 2022). NAPs often align their activities with the five objectives proposed in the GAP: to raise awareness of the problem, strengthen research and surveillance, reduce incidence of infections, optimise the use of antimicrobials, and increase investment in interventions (WHO 2015).

NAPs vary in length, breadth, content and detail (Green and Desbois 2025), with the documents generally starting by presenting the national context on AMR and the challenges faced, and this may include antibiotic-usage and AMR-prevalence data. Then, the NAP provides details for the government’s plans, which are often divided into the strategic (i.e., goals, objectives, and priorities), the operational (i.e., specific activities and interventions, implementation and responsibilities, and budgeting and costing), and the monitoring and evaluation plans (i.e., performance indicators, targets, timelines, data collection and reporting) (Green and Desbois 2025).

Some NAPs lack comprehensive details of implementation, particularly concerning who is responsible for an activity and who will shoulder the cost, and such detail may or may not be covered within further documents. Moreover, some NAPs may have overlooked certain sectors or prepared the documents in the absence of important stakeholder consultation, meaning plans for certain sectors fail to accommodate sector needs appropriately (Willemsen, Reid, and Assefa 2022). Notably, NAPs vary in how effectively they have covered actions relating to aquaculture (Caputo et al. 2022; Desbois et al. 2025). However, more recent generations of NAPs have taken steps to address such shortcomings and nowadays the documents are far more comprehensive in their coverage and finer detail (e.g., see Government of Ireland (2021) that explicitly states the new inclusion of aquaculture in the latest NAP). Still, there remains scarce explicit reference in NAPs to the use of antibiotics in the trade of ornamental species despite the One Health risks associated with the emergence of resistance and the use of critically important antimicrobials in the sector (Au-Yeung et al. 2025; Larcombe et al. 2025).

How may NAPs affect those with roles in the sector?

NAPs are drivers for change and many actors involved in the aquaculture sector may be impacted by their contents (Figure 2). The ramifications of a NAP on individuals will depend on their roles and responsibilities: It is possible that a NAP has affected workplace activities already without those people affected necessarily being aware of the link. As NAP implementation is led primarily by government through various departments and agencies, one may become aware of impending changes through communications issued by trade or professional bodies, and governmental agencies.

Common types of activity arising from NAPs include actions to reduce the need for antimicrobials, such as improved biosecurity and husbandry practices, and steps that encourage the development and application of prophylactic measures such as vaccines, probiotics and bacteriophages (Department of Health and Social Care 2024; Table 1). Other actions found commonly in NAPs are those that seek to enhance antimicrobial stewardship and ensure that where antibiotics are required their use is responsible; for example, this may be achieved by improving training provision and introducing legislation to implement greater controls on the supply of antibiotics or their use, such as banning or restricting prophylactic application (Inter-Agency Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance, n.d.; Ministry of Health and Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, n.d.; Table 1). Some plans will include steps to collect more data, such as sales volumes of antimicrobials and surveillance initiatives to monitor residues in food and the prevalence of resistant strains (Ministry of Health and Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, n.d.; Table 1). Other typical actions proposed to tackle AMR in aquaculture include the development of standard protocols to assess resistance of aquatic animal pathogens or provide a better understanding for the emergence and transmission of resistance (Table 1).

Final remarks

New NAPs are developed regularly, and a draft version of the updated GAP can be expected imminently, which will likely stimulate a new generation of NAPs across the world in the next few years. NAPs are evolving from documents describing actions that can mitigate AMR into documents that contain far greater detail for how actions will be implemented and evaluated. Those working in the aquaculture sector will benefit from heightened awareness of relevant NAPs, as it will allow for the anticipation of changes in policy and for effective planning by aligning activities with NAP objectives. Moreover, greater awareness will open up opportunities for stakeholders and actors to contribute to and influence the content of newer versions of NAPs. NAPs are the coordinated global approach to AMR and our best approach to tackling this global challenge effectively, but incorporation of aquaculture into NAPs can be improved (Desbois et al. 2025) and wider awareness for these documents within the sector should support this goal. It is vital that the aquaculture sector responds to AMR through active engagement with NAPs: Antibiotics are essential medicines and ensuring the often-limited arsenal permitted for use in aquaculture (Luthman et al. 2024) remains effective is a key responsibility for those working in aquatic animal health.

Conflicts of Interest

APD and AP sit on the Editorial Board of the Bulletin of the European Association of Fish Pathologists but they had no involvement in the handling of this manuscript including the peer-review process.